Every time I see my grandmother, she offers me something of hers—a piece of jewelry, a kitchen tool, old clothing, unfinished quilts. She and my grandfather, both in their early seventies, have been slowly, half-heartedly going through their things for the past few years. The morbidity of this gets under everyone’s skin, but my grandparents know that their things will be perceived as a burden when their time comes.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately as I prepare to move across the country with my partner, leaving behind my home of four years. It’s rare, I think, for a student to remain in place for so long, and I’ve come to think of this little condo as a truer home than any other I can imagine. It is here that I had my first kiss, my first heartbreak, my first love, my first and second degrees, and my first real job offer. This place has been one of great beginnings and so seems it should be immune to endings.

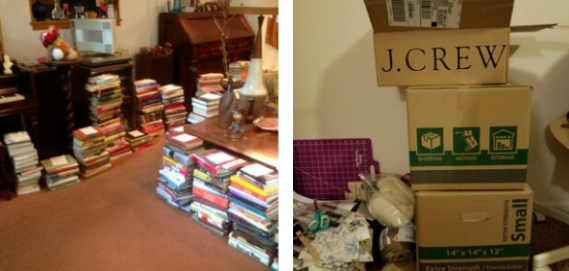

Packing has brought this all to the surface. More than signing a contract for a job on the West Coast and searching for a new apartment, loading boxes with books, securing all my old pictures and keepsakes, and wrapping up sewing projects to reduce my fabric store has bestowed upon me a sense of great loss that, at times, starts to overwhelm the sense of opportunity and adventure with which it is at odds.

A couple years ago, my mother was cleaning house and purging my little sister’s toy hoard. Some things, surprisingly many for a six-year-old, my sister parted with willingly, expressing hope that it would go to a child who didn’t have as many toys as she did. But when my mom held up other things asking if they could go, my sister would say, “But that’s my memory!”

My sister knew the exact provenance of each of these items, and her language expressed a fear that loss of the thing would mean loss of the cherished memory. In spirit of this, I’ve been taking more pictures of my partner and our cats in situ as our moving date approaches. I’ll give up most of the things in favor of a cheaper move to a smaller space, but the pictures honor the fact that my memories and emotions are bound up in the material world around me.

This is about as saccharine as I get. I get the warm-and-fuzzies taking and returning to these pictures. I’m even sort of happy to hold on to the bad memories in a strange way. That might sound silly to you, and if it does, we’re—together—probably getting a glimpse of the emotional distance that can make it unbearable to go through another person’s things.

Renowned cartoonist Roz Chast felt great frustration upon cleaning out her parents’ apartment when she moved them into a retirement home. In her graphic memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant (2014), she writes, “The knickknacks could all go to hell, along with my grade-school notebooks. I left thousands of books and records and manual typewriters and appliances and grimy liquor glasses that were probably last used in 1962.” The list goes on.

This segment of the book catalogs heaps of “junk,” much of it photographed. This is significant only because these pictures, the pictures of junky and useless things, are the only photographs in the book. Everything else, including the nine things Chast chose to keep, is drawn. These photographs depict a distance from most of the contents of her parents’ home that she does not have to the few items she keeps or to the remembered experiences with her parents themselves. While her cartoons show artistic and interpretive engagement, these photographs depict lifeless, meaningless objects.

Chast is disgusted—far beyond simply annoyed—at the task of disposing of her parents’ things. And this is fair! Who knows how I’ll feel when that time comes for me? I certainly can’t pass judgment on the feelings and behaviors of someone going through a hard time that, for me, is still a few decades away. However, her feelings do interestingly run counter to the thinking of culture theorist, and what I’d like to call “thingologist,” Bill Brown.

Brown believes that “we begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us … . The story of objects asserting themselves as things, then, is the story of a changed relation to the human subject and thus the story of how the thing really names less an object than a particular subject-object relation.”

In A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature, Brown writes about his interest in “the slippage between having (possessing a particular object) and being (the identification of one’s self with that object). It is a book about the indeterminant ontology where things seem slightly human and humans seem slightly thing-like” (emphasis in original).

Brown doesn’t explicitly express interest in the relationship between death and accumulated things, but I think the “slippage” he describes is at the heart of that issue. Objects have “a vertiginous capacity to be both things and signs (symbols, metonyms, or metaphors) of something else,” he writes. Just as Addie’s coffin in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying is a metonymic figure of Addie herself as far as her children are concerned, the “things” left behind by our loved ones can represent their histories, their personalities, and their relationships.

In other words, my sister’s bright pink teddy bear with a My Little Pony t-shirt is just that, but it’s also a reminder of her trip to the beach with our brothers, a time of great and meaningful joy in the few years she had to this point. The stairs on which my partner now occasionally sits with our kitten are a practical, architectural feature of our home, but they also hold the energy of the moment when I sat there with a one-time best friend, telling her about my excitement about my partner before he was my partner.

Sally Greene’s essay “Estate Sale,” published in the 2019 collection Mothers and Strangers: Essays on Motherhood from the New South edited by Samia Serageldin and Lee Smith, aligns much more closely with my vision of the importance of “things.” The essay is an emotional account of the process of preparing her mother’s home for an estate sale, a reflection on mother- and daughterhood, and a retrospective on her mother’s life. And all of this comes out of the process of sorting the stuff of a lifetime.

I asked about the “thingness” of the essay in an email to Greene, who told me that Lee Smith’s “welcome response [to the essay] was that it’s ‘an essay in things’! That response pleases me, because it means I succeeded in reflecting something essential about my mother, i.e. that she cherished the concrete world around her.”

I’ll admit that I was skeptical upon first reading this. In Greene’s essay “Estate Sale,” I was touched by the “tangible evidence” of her relationship with her mother. “In her closet, she kept some two dozen shoeboxes of letters from me,” Greene writes. “from college until the 1990s when a combination of my marriage, a baby, and the advent of e-mail spelled their demise.” However, like Chast, I doubted that the piles of knickknacks could be anything more than junk. But Greene gives them an almost sculptural presence: “A metal piggy bank with garish red eyes, a sand dollar, an old plastic fan, and a pair of tiny ceramic Dutch clogs combine with a small French tray to make an artful, whimsical vignette in a shuttered wooden cabinet, hung above a toilet. In such ways did objects that I might have cast aside gain new luster for being loved again.”

This certainly doesn’t mean that Greene kept all of her mother’s belongings, but upon sitting with Greene’s words in the essay and in her email to me, I realized the importance of the love and sense of discovery that she took to her potentially maddening task. Rather than viewing this job as a burden, Greene thought of it as a chance to reflect on her mother’s life and their relationship, to reconsider what it means to be alive in the world. I’ve felt this before when viewing my grandparents’ shelves of framed pictures, but I know now to bring this understanding to the once-bizarre stacks of stuffed animals, cases of figurines, and drawers of old hobby items.

In another essay titled “First Flight,” Greene theorizes her mother’s attachment to things, reminding us of its significance. “Two things you ‘ignore at your peril,’ I find her writing to me more than thirty years ago: “the dailiness of life and the significance of place.’ Texas happened to be her place. But I don’t think she ultimately meant that Texas had to be my place. Enfold yourself in the world around you, she was saying. Imperfect as it is, it is filled with beauty and surprise, and it’s all that you know. Hold it close. Hold on to it as long as you can.”

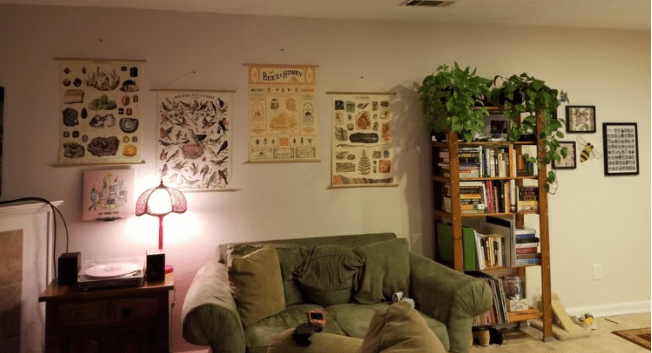

This goes against popular strains of anti-materialist thought, ideologies to which I never subscribed but by which I accidentally lived. At the beginning of our relationship, my partner poked fun at my “extreme minimalism.” I had ugly but serviceable furniture including some very full bookshelves, but that was about it. I had nothing on the walls. I felt a vague sense of embarrassment, then, and printed and framed some photos to liven the space up a bit. With my partner’s help, we slowly covered the walls in art and the floors in rugs. Now, I don’t say, “I’m heading back to the condo” like I did the first year I lived here. Instead, I say “I’m going home.”

Maybe one day those who are charged with emptying my house will roll eyes at things that now make me smile. That’s okay. Our subject-object relations will not be the same. I don’t expect them to cherish my things, but I hope they’ll understand that I have.